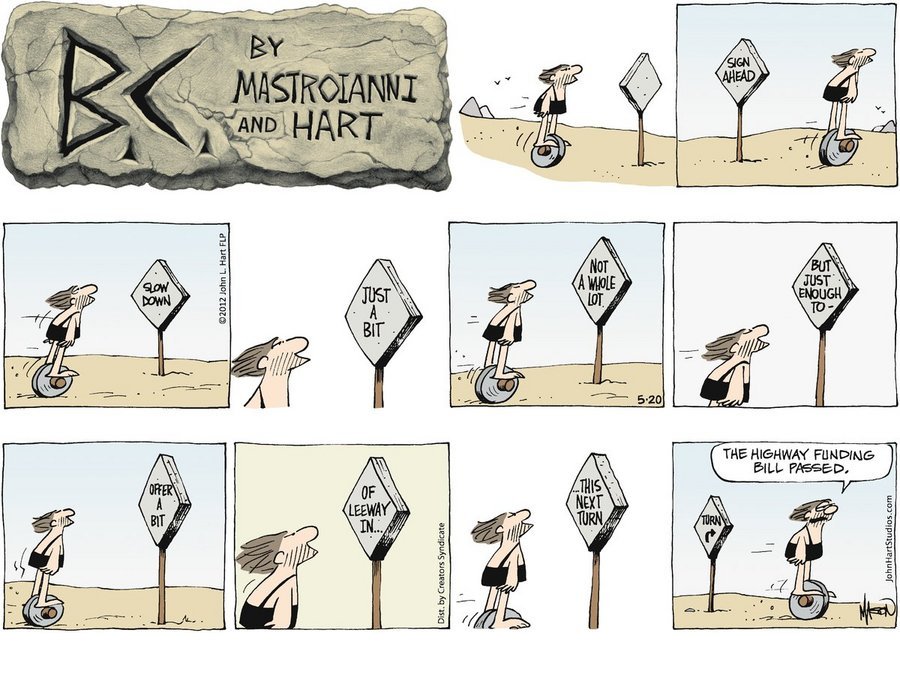

what are

signs?

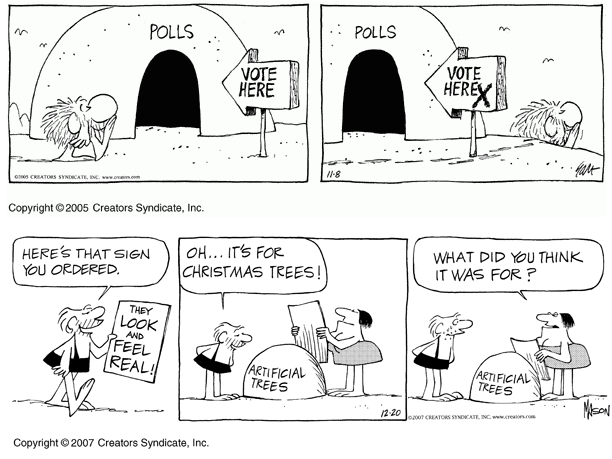

"Signs" refers to a great number of verbal, symbolic or figural markers. Posters, billboards, graffiti and traffic signals, corporate logos, flags, decals and bumper stickers, insignia on baseball caps and tee shirts: all of these are "signs." Buildings themselves can be signs, as structures shaped like hot dogs, coffee pots or Chippendale highboys attest.

They identify. They direct and decorate. They promote, inform, and advertise. Signs are essentially social. They name a human activity, and often identify who is doing it. Signs allow the owner to communicate with the reader, and the people inside a building to communicate with those outside of it.

Signs speak of the people who run the businesses, shops, and firms. Signs are signatures. They reflect the owner's tastes and personality. They often reflect the ethnic makeup of a neighborhood and its character, as well as the social and business activities carried out there. By giving concrete details about daily life in a former era, historic signs allow the past to speak to the present in ways that buildings by themselves do not.

Signs also change to reflect trends in architecture and technology: witness the Art Deco and Depression Modern lettering popular in the 1920s and 1930s, and the use of neon in the 1940s and 1950s.

a little bit of

history

From 3000 B.C. and for more than 4,000 years thereafter during the Egyptian, Grecian and Roman civilizations, and on through the Middle Ages, the use of advertising displays at the place of business constituted the only important and effective advertising medium. Tradesmen's signs were prevalent in ancient Egypt and Greece. They were widespread in early Rome - sometimes painted, sometimes carved in stone or designed in terra cotta. One of the most widely used signs in Rome was a bush of ivy and vine leaves, associated with Bacchus the God of Wine, and attached to a pole to identify a tavern. Most Roman shops displayed a sign of some sort, and many were uncovered in the ruins of Pompeii and other cities.

After the Dark Ages, exploration and trade expeditions clearly enlarged the commercial world. It was a prosperous era in business. Wealth encouraged the arts, and talent found expression in painting, architecture and literature. Merchant's signs in England, France and Italy began to come under artistic influences and reflected novel designs and colors. The signs were a means of expression for many artists, and involved elaborate carvings, gilt and paints. It is important to note that from the beginning of tribal life up to the middle of the 18th century there is no record of any advertising medium in use except that of criers and on-premise signs and displays. Advertising was strictly an outdoor medium used to designate the point of sale and the types of goods sold. In addition to the economic value of signage of all kinds as we know it today, signs have reflected man's culture since these earliest centuries.

signage in

america

Signage today is far better than it's been at any other point in history. A century ago, sign design wasn't a profession to speak of; the signs that guided riders and pedestrians (there weren't many drivers yet) tended to be informal and ad hoc. As the automobile took off, the world found it needed traffic engineers, and it was these men and women who were the first to think seriously about sign systems. America put national standards for road signs in place in 1935.

The 1970s saw the first stirrings of revolution in the sign world. That's when the Society for Environmental Graphic Design (SEGD) was founded, and it's when designers first began to seriously study how best to orient people and guide them through space. The field earned a name "wayfinding." By the 1980s and '90s, wayfinding advocates were involved in more development projects, but dispatches from the era have a slightly aggrieved air; designers of environmental graphics still often found themselves fighting for a place at the table. During the last 10 years, however, wayfinding has come into its own.

Why has there been such growth in the field? One cause is the remarkable pace of economic development over the past half-century. Developed countries have been building increasingly complicated spaces-shopping malls, multiplexes, convention centers, multi-terminal airports-that require good navigation systems in order for people to use them. In addition, businesses and municipalities alike have realized that well-oriented people are calmer, happier, and more likely to spend money (and plan return visits) than people who are lost. Investing in a good wayfinding system has real financial rewards.

The 1990 Americans With Disabilities Act was the first piece of national legislation to mandate the accessibility of privately managed public spaces like hotels and universities. And because the law deals with visual as well as physical impairment, its accessibility guidelines require that standards of legibility be maintained in directional signs; they evolved to specify everything from the size of fonts to the contrast between lettering and its background. This development turned out to be as useful for the rest of us as it was for the legally blind.

Finally, there's the fact that we have all increasingly become connoisseurs of good design. Fifty years ago, design belonged to designers. But the advent of the personal computer introduced us all to fonts, line spacing, and page layout, and machines from the photocopier to the iPhone have left us familiar with icons both clear and confusing. Navigating the Web has made us smarter about orienting ourselves in virtual space. As a result, when we see badly designed signs, we demand better.